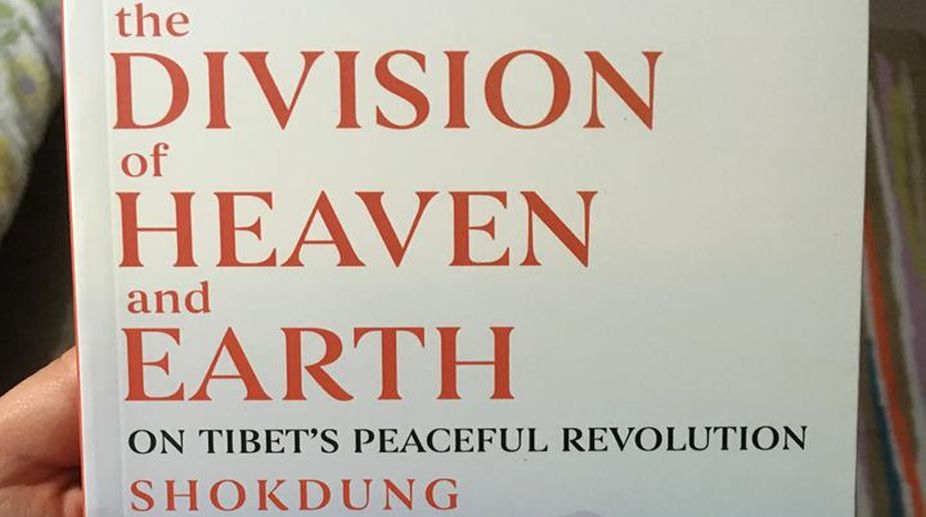

The Division of Heaven and Earth not only relates to the struggle of the courageous Tibetan people who took part in a large-scale uprising in the Spring of 2008 on the Tibetan plateau but it also brings a different perspective on the tragic fate of the Land of Snows.

Though Tagyal, writing under the pseudonym Shokdung, has lived his entire life under an authoritarian regime, he is convinced about some positive aspects of the Marxist revolution.

On 2 May 1999, on the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the 4 May student revolution in China, he published an article in Qinghai Tibetan News, titled “Blood-letting to kill the tumour of ignorance”, using the Marxist theory to argue that “the new cannot be established without destroying the old”. For him Tibetan society and culture were backward, and in order to evolve further “the ingrained influence of Buddhism on Tibetan attitudes must be wiped out.”

At that time, the article provoked a fierce debate in Tibetan society.

But when The Division of Heaven and Earth was published in China, the government was displeased; it immediately banned the book and Shokdung was arrested. As the preface puts it, “But now that he has antagonised the Chinese state and Tibetan society in different ways, this book can be seen as a milestone marking his move into political opposition.”

This makes Shokdung’s work all the more interesting. An important issue, which has been ignored by most students of history of the 1962 India-China War, is the Tibetan factor, which greatly hampered a longer conflict with India. In early 1962, the population of the high plateau had begun showing strong signs of discontent. It was manifested by a 70,000-character petition sent by the Panchen Lama, then the most senior Lama in Tibet, to the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in April 1962.

In September, one month before the war, during a CCP Conference, Mao denounced the “poisonous arrow” sent by the Lama and called him “an enemy of our class”. Tibet was in a state of unrest and that certainly shortened the war.

Already on 11 March 1959, the entire population of Lhasa had revolted to protect the Dalai Lama who had been “summoned” by the Chinese General commanding the PLA in Lhasa to attend a play inside the Chinese camp “without his escort”.

A week later the Dalai Lama, escorted by a band of some 200 brave Khampas, took the road to exile in India. In September 1987, a few days after the Dalai Lama presented his Five Point Peace Plan to the US Congress in Washington DC, riots erupted again in the Tibetan capital.

Unrest continued sporadically during the following two years, to deteriorate further in March 1989 after the massacre of more than 400 Tibetans near the Central Cathedral on 6 March. Martial law was subsequently imposed for a year. The Chinese State learned its lesson; it installed sophisticated video cameras strategically all over Lhasa and other large cities in Tibet.

That did not stop 500 monks of the Drepung monastery, commemorating the 49th anniversary of the 1959 uprising, to demonstrate on 10 March 2008. Shokdung analysed this important event using historical examples to argue his views.

At the end of the 1940s, “Finally the Tibetans, who seek spiritual perfection for all living beings, became aware of the rest of the world, and arranged to send a delegation abroad. …The land and people of Tibet appeared to stand for nothing and no one in particular, like a fox riding on a tiger’s back, at which anyone could aim a kick, and so it has remained until now: a country of nobodies, sitting idle after banging the drum in celebration of their own defeat.”

He has strong words for the prevailing political system at that time, “a history of repeated capitulation, sectarian conflict, priestpatron alliances and closure to the outside world.”

While the world around spoke of “liberation”,“the Tibetans were stuck in their pursuit of religion, and through seeking protection in the political sphere, failed to secure their own political interests.”

The authoritarian system imposed by China and the Tibetan “aspirations” eventually led the author to jail.

His ideas are unusual for an outside reader – “our largescale peaceful revolution …is a sure sign of a new awareness of nationality, culture and territory.This revolution … was like a stone thrown into a pond, sending ripples out in all directions.”

He sees the spontaneous 2008 uprising as a waking up of the Tibetan nation to its own identity, which was earlier centered on Buddhism alone. Shokdung claimed that for a thousand years, the Tibetan people had been taken in by the “Non-Self” doctrine of Buddhism, thereby losing their own “Self”, “Therefore, unless the engrained influences of the Buddhist ‘Non-Self’ on the Tibetan psyche were erased, they would never realise the ‘Self’ of imperial territoriality and ancestry.”

The Communist regime was obviously not pleased by this hidden nationalism, but interestingly his beliefs are also far away from the discourse of the Tibetan diaspora.

(The reviewer is an expert on China-Tibet relations and author of Fate of Tibet)