Prison narratives of freedom-fighters invariably document state-sponsored torture, violent and macabre expressions of sadism and diabolic humiliation of the incarcerated individual. Of course the synonyms that the State uses to suppress rebellion against it describe freedom-fighters as terrorists and insurgents. Semantic jugglery plays a dominant role to ensure and enforce the hegemony of a ruthless State administration. In colonial India linguistic subterfuges were often used by the British to quash challenges to its imperial designs and uninhibited exploitation.

In the three decades of the 20th century, many young people in India and specifically in undivided Bengal strongly felt that only an armed struggle against the British imperialists could liberate the country from the clutches of the foreign power. Apart from a bid to smuggle in revolvers, Barin Ghosh launched the Bengali newspaper Jugantar, that criticised British rule in India. When he was arrested and detained in the Alipore jail he plotted a jail break, which failed but this act of daring defiance expectedly earned the ire of the State.

The accounts, documented or fictionalised, of the experiences of the detainees in the state-controlled prisons, whether it is about the infamous remote island of St Helena where Napoleon the Emperor of France was imprisoned by the British, or the Devil’s Island, French Guianci, Alcatraz prison island in California, Auschwitz in Krakow and other German concentration camps, Guantanamo Bay prison, the US prison of Abu Ghraib in Iraq. The graphic narratives of trauma and inhuman brutality bear evidence of the physical and psychological torture to which the political prisoners were subjected.

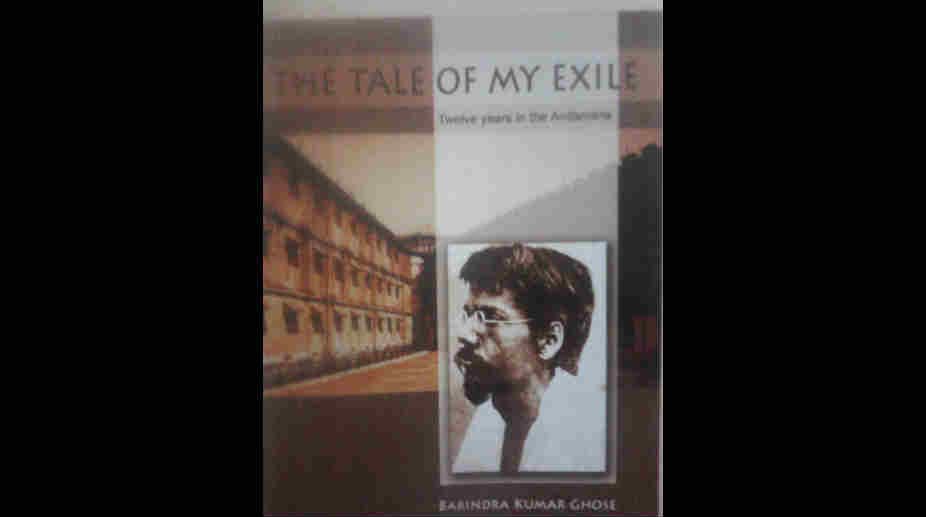

In The Tale of My Exile — Twelve Years in the Andamans, Barindra Kumar Ghosh, younger brother of the revolutionary turned spiritual guru Aurobindo Ghosh, documents in chilling detail his life as a transported prisoner serving life term at the notorious Cellular jail in the Andamans. The location was known as the dreaded black waters, Kala Pani, the isolated Cellular jail. Barin Ghosh was sentenced to death by the court on 9 May 1909 for his involvement in the Alipore Bomb case while his elder brother Aurobindo Ghosh, also arrested, was acquitted. On 23 November 1909, the death sentence of Barin Ghosh was commuted to life imprisonment in the dreaded Andaman Cellular jail.

Barin Ghosh was a prisoner in the Cellular jail from 1909 to 1920. After the end of World War I, the British government in an amnesty Act passed on 23 December 1919, granted freedom to some selected political prisoners. Barin Ghosh was one of those who had been set free.

The Tale of my Exile is not a diary or a chronologically organised memoir of the 12 years that Barin spent in the Cellular jail as a political prisoner. However, his sense of trauma and bewilderment are clearly understood from the very opening lines of the tale that is written in retrospect, recalling in abstract descriptions and comments, the horrendous experience of living death. So in the first page, Barin Ghosh wrote matter-of-factly about his hazy “memory” — “This faculty seems to have fallen into a moribund condition and can only groan at its best”. Past events can only be recalled as “shadowy and uncanny images, as it were, parading in a drunken brain.” (p1) And yet, the sense of wit and humour sometimes burst forth despite the descriptions of inhuman treatment, “What a funny spectacle we must have offered then! A wooden ticket dangling from an iron ring round the neck — just like the bell that is hung on to the neck of a bullock — fetters on the leg…” (p 7)

The 12 chapters of the narrative describe the life of the ordinary convicts and the political prisoners, the latter being the worst sufferers as they were considered to be much more defiant and consequently dangerous.

Barin Ghosh describes in detail the Bri-tish jailers, supervisors, wardens and security guards. He also describes how nauseous it was for the inmates to have the same food of “rice, dal and kachu leaf” throughout the 12 years of their stay. Also the lack of human contact, companionship and conversation reduced some of the prisoners to brutish beasts; some even indulged in sexual perversity while many became mentally unstable.

Moreover the relentless hard work of coir twisting, oil grinding and other manual labour for long hours made their stay in the penal colony insufferable. In chapter 11 titled, “A Summary of Sorrows”, Barin Ghosh observes with resignation about his life in the Cellular jail, “It will unhinge any man even in ordinary circumstances, not to speak of a prisoner, to be so hunted and insulted all the 24 hours. It is quite an inevitable eventuality that many should try to find release through suicide. Those only whose hearts have turned to stone can bury their pain and count their days in the hope of a future” (p 131).

In his outstanding, well-researched introduction the editor Sachidananda Mohanty informs readers that Barin Ghosh was a prolific writer who had published 20 books after his release from the Cellular jail, in 1929. After his release, Barin Ghosh started an English weekly The Dawn Of India, worked for The Statesman, and later became editor of the Dainik Basumati in 1950. Soon after his release he spent long years at the Pondicherry Ashram in close association with his brother Sri Aurobindo. The spirituality of the brothers Aurobindo and Barin made them transcend the challenges of a deeply complex political situation in colonial India.

Barin Ghosh wrote several riveting accounts of his experiences at the Pondicherry ashram, an abode which gave him hope and spiritual strength after the experience of traumatic living-death inside the Cellular jail. Mohanty urges the readers of Barin Ghosh’s The Tale of Exile to familiarise themselves with such path-breaking texts dealing with the repressive state apparatus such as discipline and punishment, political prisoners in India, penal settlement in Andamans, among others. By resurrecting an ignored, neglected and lost memoir, which documents the anti-colonial struggle, strangely often elided by post-colonial theorists and critics, Mohanty has drawn our attention to a neglected area of research that demands serious engagement.

The reviewer is former professor of English, University of Calcutta