Fragile Victory

The recent recapture of Sudan’s presidential palace by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) is being heralded as a significant milestone in a brutal conflict that has devastated the nation for nearly two years.

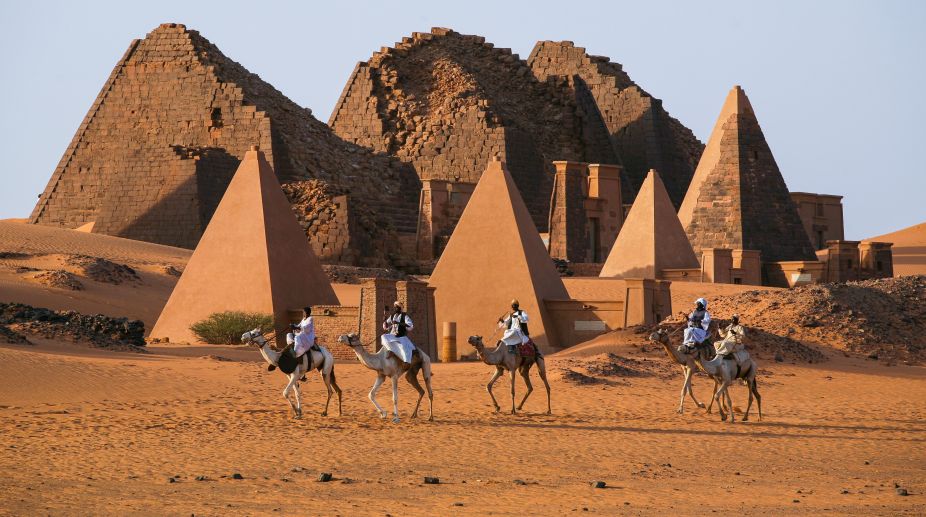

PHOTO: Getty Images

Sudan has more than twice the number of pyramids you’ll find in Egypt. I know — I couldn’t believe it either, and had to see for myself. Mention Sudan and most travellers will admit to dismissing it as a war-torn stretch of bland desert — plagued by the genocide and refugee crisis in Darfur and the ongoing civil war in the new Republic of South Sudan following a north-south split in 2011. Yet most of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office map of the country is a lovely shade of (safe) green.

But the promotion of African antiquities isn’t a priority for Omar al-Bashir, president of Sudan since his successful military coup in 1989. It’s up to travellers to take the initiative. Indeed, with Egypt still recovering from a huge slump in visitors following a series of high-profile air crashes, Sudan makes the ideal alternative — with the added bonus of zero crowds or touts.

Advertisement

I leave the rickshaws and yellow taxis of Khartoum, the capital, to drive north on a slick belt of Chinese-built, tarred road towards Soleb — an ancient town of tombs and pyramids that is home to the Temple of Soleb, one of the best-preserved temples left in Sudan. Here, on the west bank of the Nile river, not a single fence bars me from entering.

Advertisement

There’s no guard posted at an admission booth and — best of all — I’m completely alone. Shards of the far past crumble all around me: towering columns, arches and walls all carved with cartouches. Built by Pharaoh Amenhotep III in the 14th century BC, and dedicated to Egyptian Supreme God Amun, it was visited by none other than sickly child-king Tutankhamun. He inscribed his name on of one the Prudhoe Lions that once guarded the entrance — now missing from the site, as it sits in the British Museum.

I follow the processional path leading from the Nile into the belly of the temple and there, high above my head (which indicates where the sand level would have been when it was rediscovered in 1844), are the names of those first Victorian archaeologists to explore the site, chiselled into the walls. But why is it here? From 3,100 to 2,890 BC, Egyptian pharaohs sent their army south along the Nile in search of gold, granite for statues, ostrich feathers, and slaves.

Reaching as far south as Jebel Barkal — a small mountain north of Khartoum — they built forts, and later temples, along the route to demonstrate their dominance over the Nubians.

The conquered region came to be known as the Kush and the Kushites adopted all aspects of Egyptian culture, from gods to glyphs. But when the Egyptian empire collapsed in 1,070 BC, the Nubians were free. However, the religion of Amun ran deep and 300 years later Alara, King of the Kush, spearheaded a renaissance of Egyptian culture, including the construction of their own pyramids. Now believing themselves the true sons of the God Amun, Alara’s grandson Piye invaded the north to rebuild the great temples, and for nearly 100 years Egypt was ruled by the “Black Pharaohs”.

At the peak of their reign, under the command of famous Kushite King Taharqa, their territories stretched all the way to Libya and Palestine. The crown of the king bore two cobras: one for Nubia, the other for Egypt.

The last great burial site of these royal Black Pharaohs was at Meroe, an ancient city on the east bank of the Nile. It’s a nine-hour drive from Soleb, but well worth it: here, there are more than 200 pyramids, grouped across three sites. I wake at dawn and, with my guide Hitam, pace across the empty dunes towards the northern site, where 43 Unesco-listed pyramids lie scattered along a ridge.

The honeyed sunlight slides down their sandstone pinnacles as it rises, and the only other people are archaeologists excavating during the cooler morning hours. Two Egyptian eagles soar overhead, silhouetted on the sand, as I stand looking across the wide plain. “Notice anything strange on the stones?” asks Hitam. I scan the bases. “That’s an elephant,” I say, surprised. “And look here: giraffe and gazelle,” he continues, pointing to different blocks. “It’s proof this area was once covered with lush grasslands. The fertile alluvial soil allowed the Kushites to grow barley and sorghum.”

On others are scrawls made by General Kitchener’s soldiers (he of the “Your country needs you” posters). They passed by en route to the bloody Battle of Omdurman, fought to avenge the death of General Gordon, who was killed fighting a Sudanese revolt against the British in 1898. By 300 AD the Kush Empire was in decline.

Dwindling agriculture and increasing raids from Ethiopia and Rome spelled the end of their rule. Christianity and Islam followed, and prayers to Egyptian God Amun faded from memory. Time may have weathered the outer stones, but as I stood alone in silence in the burial chapel that morning, running my fingers across the well-preserved hieroglyphs, I marvelled at the realisation I was touching the same grooves Kushite workers chiselled all those aeons ago.

The legends of the kings and queens live on — and their wish of immortality will be granted if tourists continue to support travel to Sudan, which is so much more than desert.

The Independent

Advertisement

The recent recapture of Sudan’s presidential palace by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) is being heralded as a significant milestone in a brutal conflict that has devastated the nation for nearly two years.

The World Health Organization (WHO) chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus condemned the recent attack on the Saudi Teaching Maternal Hospital in El Fasher, Sudan, which resulted in 70 deaths and 19 injuries.

Rajya Sabha MP Swati Maliwal on Monday launched a scathing attack on the AAP-led ruling government in the national capital over the infrastructure and basic amenities in Delhi, saying that they don't need to make Delhi like "Africa's Sudan."

Advertisement