Balmiki Pratibha takes the final bow with its 100th act

On Sunday, 17 November, Rabindra Sadan witnessed the 100th and final staging of Balmiki Pratibha, Rabindranath Tagore’s timeless tale of redemption.

Are our campuses eco-friendly? How environmental conscious are students, administrators and other stakeholders in the educational sector? Do policy-makers consider environmental issues while formulating educational policies for the nation? Are we sensitising our younger generations to environmental challenges of the twenty first century? These oft ignored questions have never been more important, especially in the current socio-political and economic set up of the state, the nation and the world at large.

Deep concern with the environment has always been an integral part of the ancient Indian educational system and philosophy. References to environmental concerns like ecological balance, environmental protection and rainfall abound in ancient sacred texts like the Vedas—Rig, Sama, Yajur and Atharva.

Advertisement

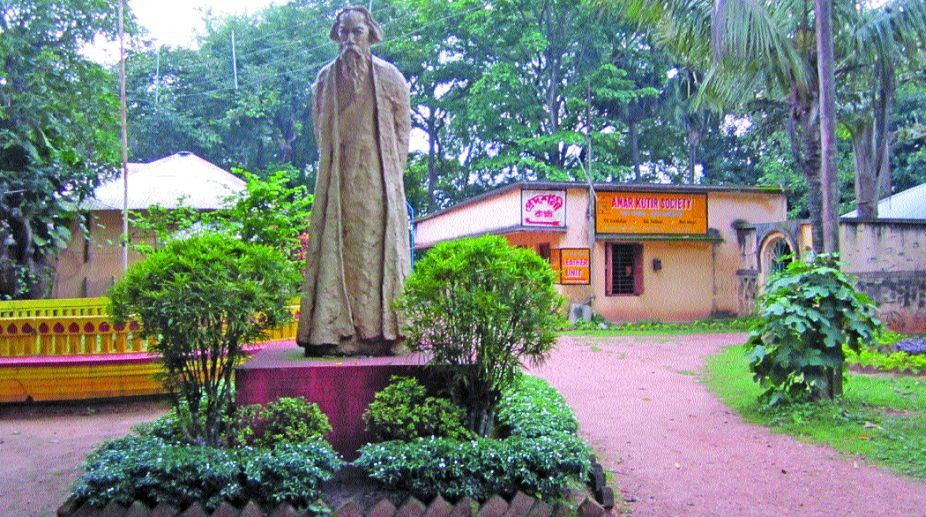

In fact, almost a century ago, it was an Indian who revived and sowed the seeds of environmental awareness with an all-encompassing altruistic, humanitarian educational philosophy for the world. Firmly rooted in the philosophy of Naturalism, Rabindranath Tagore’s establishment of Visva-Bharati University (formed in 1918 but formally inaugurated on 23 December 1921) espoused the cause of internationalism, peace, universal brotherhood, cultural co-operation and scientific excellence while drawing inspiration from the ancient gurukul system of education. Hand in hand with Santiniketan, Tagore’s establishment of Sriniketan paved the way for rural regeneration and empowerment. Officially inaugurated on 6 February 1922, with Leonard Elmhirst as its first Director, Sriniketan or the Institute of Rural Reconstruction was established at Surul – about three kilometres from Santiniketan. The primary purpose of the project was to assist the rural folk to evolve their own solutions, leading to rural reconstruction.

Advertisement

Gandhiji’s philosophy of ‘Basic Education’ apart, the success stories of Santiniketan and Sriniketan (both of which continue to flourish even today) unfortunately failed to inspire and serve as worthy instances for emulation in other parts of the country. It fact, today both these institutions strive to carry on the legacy of championing environmental concerns along with rural regeneration, with the same zest and vigour with which these ideals were mooted in the early decades of the twentieth century.

It was in the middle of the nineteenth century that Maharshi Debendranath Tagore found solace and serenity in Birbhum. In all probability in 1862, he came across a landscape that struck him as a perfect place for meditation. Enthralled by the serenity and variegated beauty of the abundantly ensconced chhatim trees and palm groves in the neighbouring villages of the Santhal tribal community, he was keen to establish a place for contemplation and quiet reflection. According to Rabindranath’s biographer Krishna Kripalani: “Soon after Rabi’s birth the Maharshi happened to visit a friend whose country estate was situated about a hundred miles west of Calcutta. Getting down at Bolpur, which was then, as it still is, the nearest railway station, he proceeded in a palanquin and as the sun was about to set found himself in an open plain bereft of vegetation, stretching to the western horizon, with nothing to break the view of the setting sun except a thin row of wild palms lining the horizon. Such open stretches are not common in Bengal where the characteristic landscape is one of luxuriant vegetation. The Maharshi was enchanted and sat down for his usual evening meditation under a pair of chhatim trees. When he rose from his meditation he had already made up his mind that the place would be his. He lost no time in negotiating for its purchase and later built a house and laid out a garden and named the place Santiniketan, which literally means an abode of peace.”

Santiniketan then constituted nearly 19 bighas of land area that was purchased by Maharishi Debendranath Tagore from the Sinha landowners. The mystical charm and meditative calmness of the location also left an indelible imprint on the mind of young Rabindranath.

Recounting his first experience of the choice of the place, Rabindranath Tagore observed in My Reminiscences: “It was evening when we reached Bolpur. As I got into the palanquin I closed my eyes. I wanted to preserve the whole of the wonderful vision to be unfolded before my waking eyes in the morning. The freshness of the experience would be spoilt, I feared, by incomplete glimpses caught in the vagueness of the dark. When I woke at dawn my heart was thrilling tremulously as I stepped outside… In the hollows of the sandy soil the rainwater had ploughed deep furrows, carving out miniature mountain ranges full of red gravel and pebbles of various shapes through which ran tiny streams revealing the geography of Lilliput.”

Rabindranath was intensely drawn to the landscape and if his son Rathindranath’s reminiscence is to be believed, the love was deeply internalised: “But there is no doubt, that (Father’s) first and deepest love was for the country of mellow green fields with their clusters of bamboo shoots swaying gently in the south breeze and hiding villages in their midst, of majestic rivers with their stretches of gleaming white sand—the haunts of myriads of wild ducks… Such associations had entered deeper into his life than the parched and barren wastes that surrounded him at Santiniketan, the choice of his later years.”

In his book Trees of Santiniketan Satyendra Basu observes that “when Maharishi Debendranath Tagore established Santiniketan the whole area is said to have been devoid of trees of any kind except in the few villages here and there which must have contained the usual type of fruit and bamboo groves etc. We can take it, therefore, that much of the greater part of the Flora now in Santiniketan and its neighbourhood owes its origin to the hand of man.’’ Basu affirms that the subsoil of Santiniketan then was a ‘decomposed grit’ that was bereft of vegetable matter, with a skeletal cover of top soil. Due to constant abrasion, this top soil had been eroded in several places exposing the subsoil which in the vicinity came to be branded as Khoai. Further erosion and subsequent weathering paved the way for gullies.

In his book, Basu conjectures about the earlier existent landscape and topography, asserting that “One presumes that there was a forest cover at one time. What was the original Flora? This must be a matter of surmise only. By analogy, it was probably a sal forest of the Bankura type. But the area was denuded of forest long ago, perhaps centuries ago…” Santiniketan in the mid nineteenth century was a weather-beaten eroded barren place. In order to enhance vegetation and revive the greenery, the top layer of coarse grainy arid earth was removed and filled with rich soil brought from outside. Such a deep concern for the environment and zest for revival of greenery should indeed serve as a lesson for future generations.

Notwithstanding the present scenario, exacerbated due to constant inflow and pressure of tourists and visitors from all over the world, even today, Santiniketan is to be celebrated as a quiet rural retreat in the lap of nature – far from the hustle and bustle of city life. Establishment of Visva Bharati paved the way for implementation of an educational philosophy deeply rooted in the school of Naturalism.

As Tagore himself had observed, “Education divorced from nature has brought untold harm to young children. The sense of isolation that is generated through the separation has caused great evil to mankind. The misfortune has been caused to the world since a long time. That is why I thought of creating a field which would facilitate contact with the world of nature.”

In order to promote deeper consciousness of nature, Tagore wanted the students to discover their potentialities under the open sky, in the midst of beautiful Mother Nature. With the larger aim of fostering and enhancing bonding with environment, Tagore introduced various events in the academic calendar in celebration of nature. These events included celebration of seasons like Vasantotsava (Spring), Varsha Mangal (Monsoon) etc.

As Krishna Kripalani points out it was during the rainy season of 1928 that Rabindranath introduced “two new seasonal festivals, Vriksha-Ropana (Tree-planting) and Hala-Karshana (Ploughing) at Santiniketan and Sriniketan respectively.” Rabindranath introduced Vriksharopana or tree planting ceremony in Santiniketan on 14 July 1928, by planting a bokul sapling. Even today Vriksharopana is celebrated on 22 Shravan (which usually falls on 7/8 August), the death anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore.

In order to enhance awareness of nature, Tagore ‘created a canon of seasonal festivals which were unique’.

Love for nature and environment pervaded even in planning of the construction of houses and laying out of gardens in Santiniketan. For instance, the planning of gardens at Uttarayan reinforces Tagore’s thoughts on environment and its conservation. These gardens, conceived by Rabindranath, were enhanced, designed and laid out by the poet’s son Rathindranath, who was a skilled horticulturist. He planted in Uttarayan and surrounding areas exotic plants and trees which he managed to get from Africa. Notable among these plants were the African Tulip from Equatorial Africa, Sausage tree, Rhodesian Wisteria from Tropical Africa, Baobab tree from Sub Saharan Africa, Caribbean Trumpet tree among several others. Akin to garden planning, nature also occupied a special role behind construction of houses like Shyamali, Konark, Punascha, Udichi and others in Santiniketan.

To sum up in the words of Kripalani: “Tagore, the lover of forests, whose favourite reading was Hudson’s Green Mansions, and who had long bewailed the ruthless deforestation of the countryside, wanted to introduce a practice which would catch the popular imagination and make people plant trees for the love of them. He succeeded. Not only is Santiniketan, which was once a wasteland of corroded soil, a miniature garden town, but the tree-planting ceremony initiated by him is now an all-India festival actively sponsored by the central and state governments.’’ It is time to revive and share Tagore’s eco-centric concerns, making our campuses eco-friendly and students more sensitive about environmental issues.

The writer is the Dean of Arts, St Xavier’s College, Kolkata.

Advertisement