China-Bangladesh relations: A new path or new worry?

Chief advisor of Bangladesh’s interim government, Muhammad Yunus was recently on a four-day official visit to China, the first bilateral engagement since assuming power.

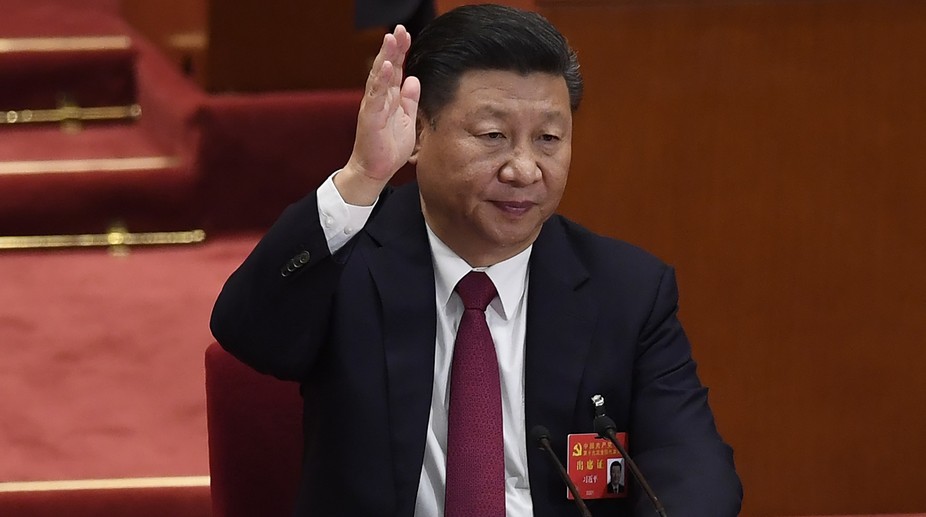

Chinese President Xi Jinping (Photo: AFP)

At the end of the 19th Congress, most of the Western media have declared President Xi Jinping, the winner. He is the most powerful leader since Mao, say the China watchers. But is it true? A great difference between Mao and Xi is that the Great Helmsman controlled the Communist apparatus without intervening much in the day-to-day affairs.

He often travelled the countryside in luxurious trains for weeks, with just a few secretaries and several of his favourite ‘nurses’. He had no encrypted way of communicating with his colleagues (or ‘lackeys’ in Maoist parlance) in Beijing. He was not bothered. This is not the case of Xi Jinping who heads a large number of Leading Small Groups on many topics under the Middle Kingdom’s sky, but he is also General Secretary of the Communist Party of China, the President of the People’s Republic of China, the Chairman of the Central Military Commission and the Commander-in-Chief of the Joint Battle Command.

Advertisement

Xi has however undoubtedly emerged as the winner on several fronts in recent months. First and foremost, the 19th Congress approved an amendment to the Party Constitution enshrining Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.

Advertisement

Though the new Central Committee and Central Commission for Discipline Inspection are more or less along the expected lines, the Politburo and the Standing Committee brought some surprises. The new Politburo’s Standing Committee now comprises President Xi, Premier Li Keqiang, Li Zhanshu, Wang Yang, Wang Huning, Zhao Leji and Han Zheng.

The presence of Li Zhanshu, Xi’s chief of staff, who is to take over the chairmanship of the National People’s Congress, is a proof of Xi’s control over the appointments. Ditto for Wang Huning, the party theorist who will take the charge of ideology, propaganda and party organization, while Zhao Leji will replace Wang Qishan, as the new antigraft tsar. Wang Yang will take the seat of Yu Zhengsheng as chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference; as for Han Zheng, he will probably be drafted as Executive Vice-Premier in March.

But where are Xi’s presumed successors, Hu Chunhua and Chen Miner? Where is Wang Qishan, Xi’s right-hand man who, for five years, arrested the ‘tigers and the flies’? The absence in the Standing Committee of Chen Miner, the Party Secretary of Chongqing, who was expected to be anointed ‘heir apparent’ has been noticeable. Apparently Xi does not want a ‘successor’ as yet. Same for Hu Chunhua, Guangdong Party Secretary, who for several years was said to be a future new General Secretary.

Just before the Congress, the South China Morning Post (SCMP) which has been by far the bestinformed, noted: “Hu Chunhua ~ the widely tipped successor ~ and the president’s protégé, Chongqing party chief Chen Miner, are both likely to be missing from the Politburo Standing Committee. Instead, they will join the Politburo, which is one rank lower.” It is what happened. SCMP had good tips, despite the opacity of the party proceedings. The great surprise was that Wang Qishan, who is responsible for making thousands of party heads roll, has stepped down from the Standing Committee, due the age-limit norm.

It was confirmed when his name did not appear in the list of the new Central Committee members. Many ‘watchers’ were expecting Xi to break an unwritten retirement-age rule to keep his friend Wang in the Standing Committee. Two members of the powerful Central Military Commission (CMC) made it to the Politburo. Apart from Air Force General Xu Qiliang, presently CMC ViceChairman, General Zhang Youxia, a family friend of Xi, was selected as the second vicechairman.

Contrary to what many have written, Xi might not be all-powerful; he still has to deal with party norms and traditions: “He is careful not to break the age rule and to follow the order of seniority. These political norms are critical for the 89-million member Communist Party to have consensus at the top and maintain stability,” wrote the SCMP which also noted: “Xi is also not blindly following the established path.” Another sign that Xi may not have full control, is the reduced size of the CMC which has only 7 members (apart from the two Vice-Chairmen: Xu Qiliang, Zhang Youxia, others are Wei Fenghe, Li Zuocheng, Miao Hua, Zhang Shengmin) compared to 11 during the previous Congress. The day after the announcement of the new CMC, Xi met the PLA delegation and urged them to “follow the road maps set for it at the Congress.”

It is easier to agree on 7 than 11. Xi said socialism with Chinese characteristics has entered a new era, and the military should make all-out efforts to become a world-class force by 2050 while striving for the realization of the ‘great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’. Xi ordered the PLA to be absolutely loyal to the party, to focus on how to win in wars, to pioneer reforms and innovation, to scientifically manage commanding a unit and to lead troops in accordance with the strictest standards. Strangely, there was no photo with the new CMC.

Another odd happening: General Song Puxuan, one of the rising star’s in the PLA and the newly appointed head of the CMC’s Logistics Support Department did not make it to the list of the Central Committee’ members. In 2014, Song was promoted to the rank of full general, taking the charge of the Northern Theatre Command, overseeing the defence of the capital and China’s border with North Korea. His failure to make it to the Central Committee is still unexplained. When the list of the delegates to the Congress was first released in July, many watchers thought that it would mark a new area for women, who made up 24.1 per cent of the 2,287 delegates. The official media pointed out that it reflected the efforts made by the party “to give women members a bigger say and improve gender equality and social stability.”

But Chinese women leaders are still practically excluded from the top of the hierarchy. Of the 204 members of the Central Committee, just 10 are women; the same figure as that for the 18th congress of 2012. And only one lady, Sun Chunlan made it in the Politburo. She will probably retain her job as Chief of the United Front Work Department.

That is disappointing. As for the ethnic minorities, they have got a slightly better deal in the Central Committee, with 16 members from ethnic origins compared to 10, five years ago. Incidentally, the Tibetans have four representatives who have been selected as members of the Central Committee (Lobsang Gyaltsen and Che Dalha) and Alternate members (Norbu Thondup and Yan Jinhai, a Tibetan from Qinghai); it is a first. Further, Wang Huning, the newly-appointed member of the Politburo’s Standing Committee will probably represent Tibet at the National People’s Congress in March. The question is why should a Han leader represent Tibet?

Han chauvinism will continue for some time more. In any case, Wang’s presence does not mean that life will become easier for the Tibetans or the Uyghurs. Chen Quanguo, the former Party Tibet Secretary presently posted in Xinjiang, has been rewarded with a seat in the Politburo for the repressive measures he introduced in the restive Muslim region.

What does all this mean for India? One will have to wait and see. As Deng Xiaoping liked to say, ‘Let us seek truth from facts’.

(The writer is an expert on China-Tibet relations and author of Fate of Tibet)

Advertisement

Chief advisor of Bangladesh’s interim government, Muhammad Yunus was recently on a four-day official visit to China, the first bilateral engagement since assuming power.

Vanessa Lloyd, chair of Canada’s security and intelligence threats to elections taskforce, mentioned recently at a press conference that India, Russia, Pakistan, Iran and China can subvert their national elections through sophisticated disinformation campaigns.

India’s rapport with Bangladesh has plummeted to unprecedented depths, with Bangladesh’s Chief Advisor Muhammad Yunus’ latest sojourn in China poised to further exacerbate the anti-India sentiment.

Advertisement