The word ethics is derived from the Greek word ‘ethos’, which means ‘way of living’. The judgement of right and wrong, what to do and what not to do, and how one ought to act, form ethics. It is a branch of philosophy that involves systematising, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behaviour.

Morality is the body of standards or principles derived from a code of conduct from a particular philosophy, religion, or culture. It can also derive from a standard that a person believes in. The word morals is derived from the Latin word ‘mos’, which means custom.

Many people use the words Ethics and Morality interchangeably. However, there is a difference between Ethics and Morals. To put it in simple terms, Ethics = Moral + reasoning.

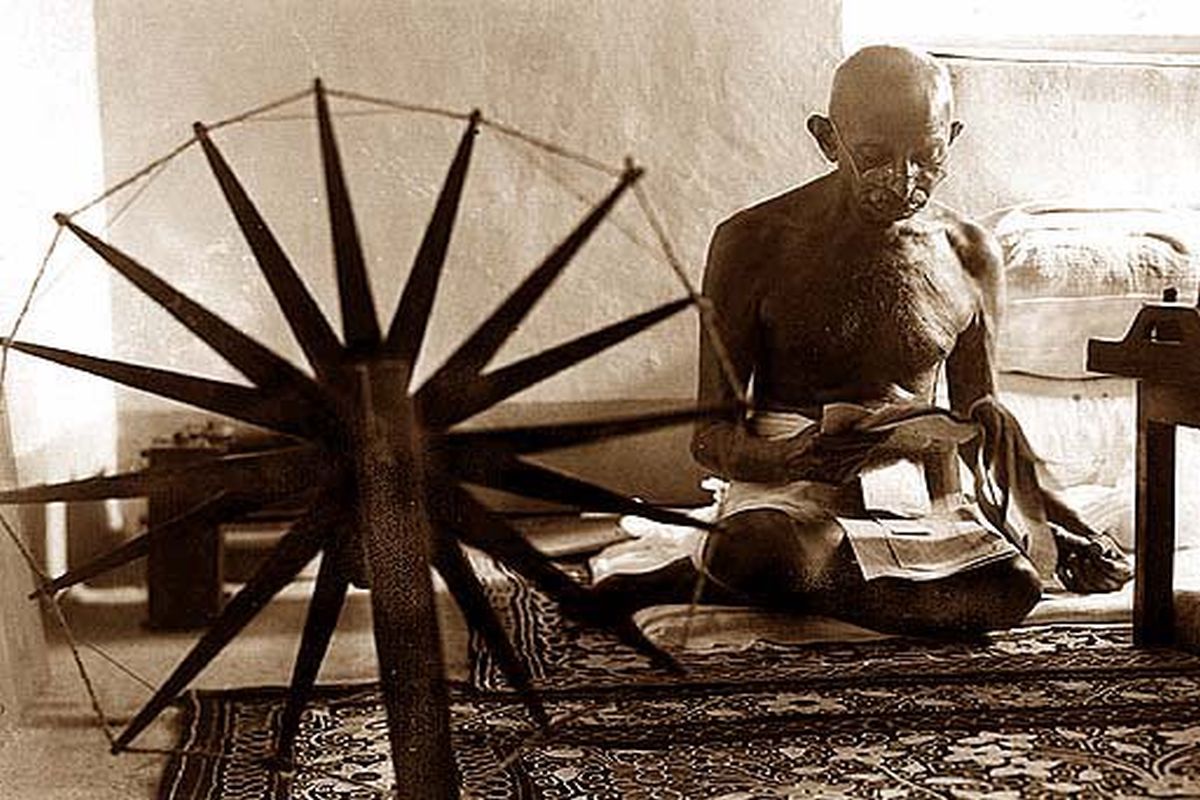

For example, one might feel that it is morally wrong to steal, but if he/ she has an ethical viewpoint on it, it should be based on some sets of arguments and analysis about why it would be wrong to steal. Mahatma Gandhi is considered as one of the greatest moral philosophers of India. The highest form of morality in Gandhi’s ethical system is the practice of altruism/self-sacrifice.

For Gandhi, it was never enough that an individual merely avoided causing evil; they had to actively promote good and actively prevent evils. The ideas and ideals of Gandhi emanated mainly from: (1) his inner religious convictions including ethical principles embedded in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Christianity; (2) the exigencies of his struggle against apartheid in South Africa and the mass political movements during India’s freedom struggle; and (3) the influence of Tolstoy, Carlyle and Thoreau etc. He was a moralist through and through and yet it is difficult to write philosophically about his ethics.

This is because Gandhi is fundamentally concerned with practice rather than with theory or abstract thought, and such philosophy as he used was meant to reveal its ‘truth’ in the crucible of experience. Hence, the subtitle of his Autobiography ~ ‘the story of my experiments in truth.’ The experiments refer to the fact that the truth of concept, values, and ideals is fulfilled only in practice.

Gandhi’s ethics are inextricably tied up with religion, which itself is unconventional. Though an avowed Hindu, he was a Hindu in philosophical rather than a sectarian sense; there was much Hindu ritual and practice that he subjected to critique.

In his Ethical Religion, published in 1912 based on lectures delivered by him, Gandhi had stated simply that he alone cannot be called truly religious or moral whose mind is not tainted with hatred and selfishness, and who leads a life of absolute purity and of disinterested services. Without mental purity or purification of motive, external action cannot be performed in selfless spirit. Goodness does not consist in abstention from wrong but from the wish to do wrong; evil is to be avoided not from fear but from the sense of obligation. Consistency was less important to Gandhi than moral earnestness, and rules were less useful than specific norms of human excellence and the appreciation of values. Politics is a comprehensive term which is associated with composition and operation of state structure as well as its interrelationship with other states. It is activity centred around power and very often deprived of morals. With its power-mongering, amoral Machiavellianism, and its valorisation of expediency over principle, and of successful outcomes over scrupulous means, politics is an uncompromising avenue for saintliness. Inclusion of ethics in politics seemed to be a contradiction to many contemporary political philosophers.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak among others warned Gandhi before he embarked on a political career in India, “Politics is a game of worldly people and not of sadhus.” Introducing spirituality into the political arena would seem to betoken ineffectiveness in an area driven by worldly passions and cunning. It is perhaps for these reasons that Christ himself appeared to be in favour of a dualism: “Give to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s.” In this interpretation, the standards and norms that apply to religion are different from those relevant to politics.

Gandhi by contrast, without denying the distinction between the domain of Caesar and that of God, repudiates any rigid separation between the two. As early as 1915, Gandhi declared his aim “to spiritualise” political life and political institutions.

Politics is as essential as religion, but if it is divorced from religion, it is like a corpse, fit only for burning. In the preface to his autobiography, Gandhi declared that his devotion of truth had drawn him into politics, that his power in the political field was derived from his spiritual experiments with himself, and those who say religion has nothing to do with politics do not know what religion means. Human life being an undivided whole, no line could be drawn between ethics and politics. It was impossible to separate the everyday life of man, he emphasised, from his spiritual being. He said, “I feel that political work must be looked upon in terms of social and moral progress.” Gandhi is often called a saint among politicians. In an epoch of ‘globalisation of selfcentredness’ there is a pressing necessity to comprehend and emulate the moralistic dimension of Gandhian thought and re-evaluate the concept of politics. The correlation between ends and means is the essence of Gandhi’s interpretation of society in terms of ethical value rather than empirical relations. For Gandhi, means and ends are intricately connected.

His contention was, “For me it is enough to know the means. Means and ends are convertible terms in my philosophy.” Gandhi countered the assertion that ends vindicate means. If the means engaged are unjust there is no possibility of achieving satisfactory outcomes. He compared the means to a seed and the end to a tree. Gandhi stuck to this golden ideal through thick and thin, without worrying about the immediate results. He was convinced that our ultimate progress towards the goal would be in exact proportion to the purity of our means.

Gandhi believed that “Strength does not come from physical capacity. It comes from an indomitable will.” His seven social sins refer to behaviours that go against ethical code and thereby weaken society. When values are not strongly held, people respond weakly to crisis and difficulty. The seven sins are: (1) Wealth without work; (2) Pleasure without conscience; (3) Knowledge without character; (4) Commerce without morality; (5) Science without humanity; (6) Religion without sacrifice; and (7) politics without principle. Gandhi’s Seven Sins are an integral part of Gandhian ethics.

The Satyagraha (Sanskrit and Hindi: ‘Holding into truth’) as enunciated by Gandhi seeks to integrate spiritual values, community organisation and selfreliance with a view to empower individuals, families, groups, villages, towns and cities. It became a major tool in the Indian struggle against British Imperialism and has since been adopted by protest groups in other countries.

According to the philosophy of Satyagraha, Satyagrahis (Practitioners of Satyagraha) achieve correct insight into the real nature of an evil situation by observing a non-violence of the mind, by seeking truth in a spirit of peace and love, and by undergoing a rigorous process of self-scrutiny. In so doing, the satyagrahi encounters truth in the absolute. By refusing to submit to the wrong or to cooperate with it, the satyagrahi must adhere to non-violence. They always warn their opponents of their intentions and forbid any tactic suggesting the use of secrecy to one’s advantage. Satyagraha seeks to conquer through conversion: in the end, there is neither defeat nor victory but rather a new harmony. Gandhi’s Satyagraha always highlighted moral principles. By giving the concept of Satyagraha, Gandhi showed mankind how to win over greed and fear by love.

There was no pretension or hypocrisy about Gandhi. His ethics do not stem from the intellectual deductive formula. ‘Do unto others as you would have them unto you.’ He never asked others to do anything which he did not do. It is history how he conducted his affairs. He never treated even his own children in any special manner from other children, sharing the same kind of food and other facilities and attending the same school. When a scholarship was offered for one of his sons to be sent to England for higher education, Gandhi gave it to some other boy. Of course, he invited strong resentment from two of his sons and there are many critics who believe that Gandhi neglected his own children, and he was not the ideal father. His profound conviction of equality of all men and women shows the essential Gandhi who grew into a Mahatma.

The question of why one should act in a moral way has occupied much time in the history of philosophical inquiry. Gandhi’s answer to this is that happiness, religion and wealth depend upon sincerity to the self, an absence of malice towards others, exploitation of others, and always acting ‘with a pure mind.’ The ethical and moral standard Gandhi set for himself reveals his commitment and devotion to eternal principles and only someone like him who regulated his life and action in conformity with the universal vision of human brotherhood could say “My Life is My Message.”