Swiggy to foray into ownership, management of sports teams business

Food delivery and quick commerce player Swiggy is setting up a subsidiary to foray into the growing demand for recreational activities.

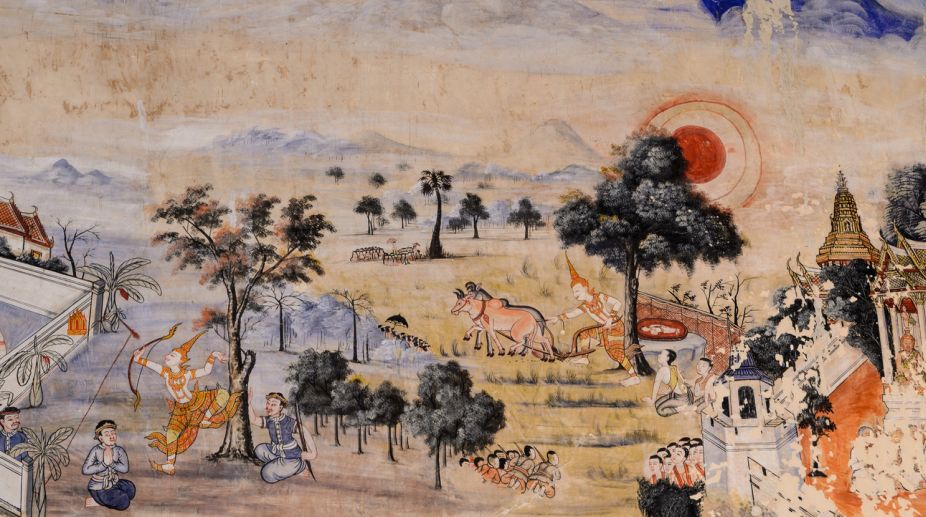

Representational image (Photo: Getty Images)

In the early 1990s Dr SK Chakraborty, professor of financial management at IIM Calcutta, made his way through the incredibly dense forest of our ancient scriptures to extract principles for setting up a new paradigm — the Indian system of management.

The corporate world responded enthusiastically, helping to set up the unique Management Centre for Human Values at IIMC. Therefore, I was surprised to find him absent from the IOC’s new publication. However, when I read the Marketing Head’s remark that this was “a coffee table book” it made sense.

Advertisement

What is being offered here is not intensive management input but a management-made easy presentation drawing upon Indian myth. The contributors are almost all the new breed of “best-selling” Indian writers of “mytho-fiction”.

Advertisement

Even there I was surprised to find Ashok Banker missing. Did he not set the ball rolling with his blockbuster heptalogy on the Ramayana? We have here 14 stories, each enunciating a principle of management, richly illustrated with striking paintings by Cina KS, though Shiva as a bald, grimacing Brahmin in tandava pose is certainly a first! Amish Tripathi leads the rest. He does not tell a story but writes on why myths stay alive, making the valuable point that liberalism can feed religiosity and the other way about.

He perceptively points out that by failing to fall in step with changing times the gods of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and the Nordic deities died out. On the other hand, in India our myths have been appropriated by the people, with every language having its own localised version.

The vibrant dynamism of Indian mythology can be seen in the many versions of myths still being telecast. Anand Neelakantan tells a tale about a bhakta missing his desired boon to be rich because he would not seize the opportunity but obstinately confined himself to chanting prayers, waiting for the goddess to rain wealth. On the other hand, Anuja Chandramouli writes about a woman savagely maltreated by her mother-in-law, abandoned by all but her brother who carries her in her last days into a ruined temple.

Here she seeks revenge from the goddess on her tormentors. But when she is made whole by the deity, instead she asks that none should suffer as she and her brother have. Management relevance? Ashwin Sanghi and Christopher Doyle are called the Dan Browns of India.

The former relates a lovely anecdote from his childhood, learning from his Munimji the significance of Ganesha being flanked by Lakshmi and Saraswati, and what the features of the deity signify. The latter draws lessons from the Kurukshetra war for team-work and organisational development.

However, most of what he says is really old MBO wine in a new bottle. Dr Devdutt Pattanaik is, of course, the first to popularise mythology as a source for management principles. From a completely novel source, Shiva’s threelegged follower Bhringi, in just two pages draws a telling lesson about the indispensability of each arm of an organisation for its successful performance.

Kavita Kane, whose novels are about the neglected women of our epics, retells a legend about Shurpanakha confronting guilt-ridden Lakshamana after he had, by mistake, slain her young son while “thrashing the long grass” in the forest. Instead of killing him, she finds that his remorse is the retribution. Krishna Udaysankar is the author of the gripping Aryavarta trilogy, a novel on the origins of Singapore and a taut thriller “Immortal” featuring Ashvatthama. First, she gives us a thoughtful two pages on why we find mythology reconstructed as fiction so appealing.

Then in two more pages she draws a brilliant vignette of Sita speaking her mind to Rama as she leaves him forever to step into the flames, with the words, “My life is my oath.” Dr Radhakrishnan Pillai’s piece is out of place in this collection as he is a Chanakya aficionado. He simply enunciates principles from the Arthashastrafor use in corporate management. So is Rashmi Patel’s long tale, running to nearly six pages, which is about a corporate executive having a dream experience during a flight in which he learns crucial lessons — too predictable — from a monk who turns out to be Swami Vivekananda. So he is a mythical figure now?

Shatrujeet Nath lends a different spin to the tragic tale of Abhimanyu, ascribing his fate to Krishna’s deliberate decision either because the god Chandra had insisted on getting his son back when he reached 16, or because he was Kansa or Kalayavana reborn (this is a variation one has not heard so far). By having Abhimanyu die, Krishna motivated Arjuna to put his heart and soul into the war.

This, of course, means that the Gita had no impact upon him — something that Nath does not deal with. From this he draws lessons on corporate strategy, which presumably needs to be ruthless in the same manner. Swami Shubha Vilas is certainly not one of the “best-sellers”. He writes on the “coachable leader” with Krishna coaching Arjuna from being “the best” to “your best”.

Utkarsh Patel has begun to make his mark with his novel on Shakuntala and his “Talking Myths Project.” He explores through stories in the Mahabharataand the complex concept of ethics.

There is some confusion here between ethics and morals. The ethics of an act may not be moral. That dimension needed to be considered. To his credit, he ends posing a crucial question, “Everything comes at a price, and so does (sic) ethics and morals.”

Vamsee Juluri appears to be new on the horizon of mythological fiction. His contribution is unusual. He presents the 1957 Telugu blockbuster movie Maya Bazaar in terms of an allegory for the world-situation today, hoping that India’s magical touch will save the world-situation, like Krishna rescuing Abhimanyu and Balarama’s daughter Sasirekha from the machinations of Duryodhana who manipulates Balarama. In all, this is certainly not a coffeetable book. There is adequate substance packed into just 90 large pages, enriched with eye-catching illustrations, excellent printing and binding. IOC would do well to make this available to the public in general.

(The reviewer retired as additional chief secretary, West Bengal, and specialises in comparative mythology)

Advertisement